Stylistically, there was also a good affinity, and Casson fit right in.

Stylistically, there was also a good affinity, and Casson fit right in.This landscape sketch captured near Rosseau, in the Muskoka region shows his chops.

Besides painting the landscapes of Ontario's 'Near North' and further towards Lake Superior, the small Southern Ontario towns and their architecture were one of Casson's favourite subjects.

Some of his views of rural buildings and simple structures reminds me of Edward Hopper. (See my MoMoArt#3 on Hopper) Certainly the magical lighting effects, and the stylized, simplified details are evocative of Hopper's work. In Casson's work the landscape is always and important element there as well.

This piece is an "Anglican Church at Magnetawan" and besides the brightly illuminating sunshine, there are the sculpted, somewhat ominous trees, a distant treeline and the river in view.

This piece, the Store at Salem also has a Hopper-esque feel to me. While the clouds and rocks and shaded contours are reminiscent of what Lauren Harris was doing too.

Ultimately, the organized Group of Seven artists disbands in 1932 - though Casson as the youngest of the group is still in his prime. He begins the "Canadian Group of Painters" in 1933. But with Harris, Carmichael, Lismer and Jackson on board, it's clearly just a (better-named) reconstitution of the same crew. (The Canadian Group on Wikipedia. Oh look, Varley, Carr etc too).

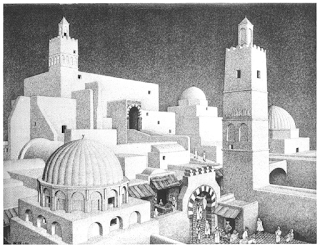

The graphics and screen-printing aesthetic of Casson's background comes through in his work. This one of "The White Village" is a good case in point.

The graphics and screen-printing aesthetic of Casson's background comes through in his work. This one of "The White Village" is a good case in point.There, the golden trees are towering over the buildings, and the water and rocks in the foreground place the houses squarely in nature. Figures are rare in his work - all the personality coming from the landscape.

I shouldn't skew this too much toward the views of small towns, as his trips into the northern bush are a key part of his work. Casson did many views of Moose lake as well.

This piece is simply "Moose Lake."

Sky at Moose Lake" as well. It's a bit more wild and lively.

Back in the urban landscape, there are a pair of pictures from around 1927 that stick with me.

These are the rooftops-in-the-snow pictures that capture well the cold, crisp, sunny days in the neighbourhood, familiar to urban Canadians.

The colour in this image of his "Rooftops of the Ward" might be a little skewed into the orange from the original, but a winter warmth comes through that is very appealing there.

His "Rooftops" in this second image has a somewhat different style. It's reminiscent of some of the Quebec artists of the time (perhaps Marc-Aurele Fortin).

Alfred Casson played an important part in the development of Canadian art in the Twentieth Century, without doubt. It's the cross-fertilization of styles from the other artists of the time that is particularly appealing.

Unlike many of the others at the time, Casson did not have a prolonged European period in his development, as far as I'm aware (though I haven't researched that in any thorough way). Many other members of the Group of Seven and the Canadian Group had, as part of their education, some time spent painting in France. Some had been born in the UK and had some exposure to the artists of that area.

Casson picked up Impressionist and Nouveau influences once removed from that scene. Perhaps that helped allow him to carve out his own unique melange of those elements.

I'll wrap up with his "General Store" (he found many 'stores general' to serve as subjects). This one intrigues me somewhat because of the magical background of ghostly blue shapes, reminiscent of Emily Carr's work.

The piled-up twilight clouds are not unlike Carr's rainforest tree-shapes. Again, structures dropped into a dramatic landscape. One gets the feeling of these outposts of humanity finding a foothold in the wilderness, but tolerated rather than dominating their environment.